Author: Reka Sulyok

The chemical sector’s global sales were around 3.5 trillion USD or about 4% of global GDP in 2020 while responsible for 5% of the total man-made CO2 emissions amounting to a total of 1.5 Gt annually. When all GHG gases considered the share is a touch higher at around 7%. The sector is clearly important economically as well as from the decarbonisation perspective.

In 2021 market for chemicals was seen to double by 2030. But the industry’s financial out-performance and great growth potential is now shattered by the gas crisis. Some of the largest companies are already bracing for multi-year strains thanks to lasting energy supply shortages. And if the previous economic crisis is anything to go by, chemical sector seems highly pro-cyclical. Even though the previous crisis was not commodity driven production nosedived by 20% in the EU. This time the stakes might be even higher as multiple factors are directly imperiling the chemical sector. Supply bottlenecks, buildup of material shortage and plant close downs already topped the news this summer.

Feeling the heat this summer

Group Azoty in Poland halted some of the basic chemical and nitrogen fertilizers production against the backdrop of rising gas prices. They reckon that natural gas prices more than tripled over the first six months of the Russian war against Ukraine. Prices sky-rocketed to €276 per megawatt hour (MWh) by 22 August from just €72 per MWh on 22 February. What’s more, last week sent Europe’s benchmark gas prices to a fresh high of €343 on Friday.

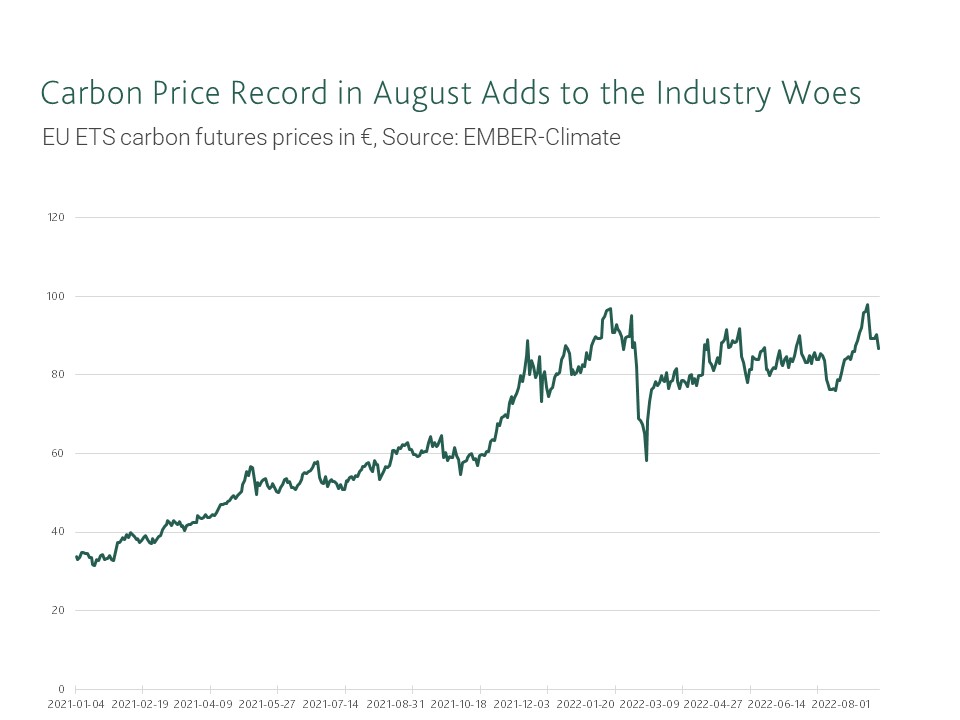

Not only the gas prices are painful. Carbon emission credits have been soaring and climbed to a record in August. Demand for ETS allowances is likely to stay strong as coal power plants coming online and need to pay for their hefty emissions. The carbon futures may indicate a bullish momentum as investors are betting on multi-year gains to come and take long positions.

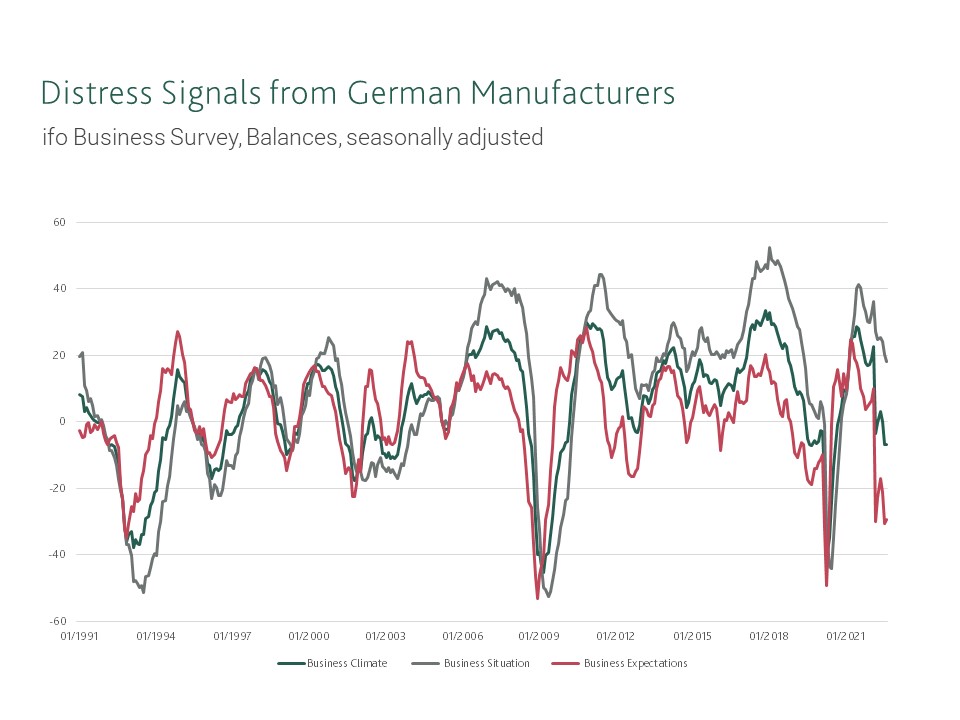

Surge in prices will surely chip away competitiveness of the European chemical industry. Sentiment in Germany who has 28.6 % share in total production in EU have been flashing signs of mounting distress. Not only did producers note rising input prices but their key markets also melted thanks to the war. But replacing trade relations amid the ongoing crisis will not be easy. IMF forecasts now that Germany’s GDP add 1.2 percent this year and slow further 0.8 percent for 2023 as exports will tumble.

The global refining sector garnered a lot more attention than its more downstream counterparts which take the refined petroleum- or natural gas- based products such as naphtha, ethane, and LPG as feedstocks. Downstream chemical production is harder to underpin out of the hard-to-abate industrial group. This could explain why the sector seem to have punched well below its weight in decarbonisation debate.

Many think that chemical sector’s emissions should be fixed at the refineries and there is a need for eliminating the fossils altogether. But that view fails to account for the basic chemical need of the global economy. More than 95% of all manufactured products rely on chemistry and that structural dependency won’t change overnight.

In a way this is the same predicament that the EU Commission is currently grappling with when drafting guidance on how to ration gas to industrial use. We see that chemical sector can get caught in the crosshairs for its undeniable vast gas consumption that is hard to sort out. The sector’s consumption on a product-by-product basis could be hard to estimate as refinery outputs and basic chemical products are very closely integrated. Not only does the sector rely on multiple processes but there is a difficulty to capture and trace all dependencies further down the supply chain. WEF noted that when the value chains are considered most emissions are made at the beginning, during the production of high value chemicals such as ammonia and cracker products. However, most of the value is added much further down the line when the final consumer products such as electronics and vehicles are produced. That is, curtailing gas consumption above can have far-reaching economic consequences.

That the aggregate information and data are scattered around different sub-sectors and geographies’ adds further complications. The chemicals sector has many associations organized on sub-sector levels. The value chain and cross border analysis the Commission proposes now can bring a positive leap forward. Ironically, rationalizing gas use in industry could help tackling the long-standing data gap that also impeded carbon management at Scope 2 and Scope 3 emission granularity. The crisis may turn attention to chemical sectors’ complexity that the Taxonomy regulation could not fully appreciate and ESG reporting frameworks too have likely fallen short of reckoning.

State of emissions

The chemical industry is represented by the Brussels based CEFIC (European Chemical Industry Council). CEFIC’s own analysis found that the seventeen most emitting products and processes are responsible for 88.6% of the total emissions of the sector. The cumulative share of emissions is proof enough that the first eight products of the list contribute the most and the marginal share diminishes significantly. Ammonia and petrochemicals (steam cracker products) appear then the two major processes from the emission perspective.

| NACE code | Product / process | Process and steam emissions [Mt CO2-equivalents] |

Share | Cumulative share |

| 2015 | Nitric Acid | 41 | 21.6% | 21.6% |

| 2014 | Cracker products (HVC) | 35 | 18.4% | 40.0% |

| 2015 | Ammonia | 30 | 15.8% | 55.8% |

| 2014 | Adipic acid | 13 | 6.8% | 62.6% |

| 2011 | Hydrogen / Syngas (incl. methanol) | 12.6 | 6.6% | 69.3% |

| 2013 | Soda ash | 10 | 5.3% | 74.5% |

| 2014 | Aromatics (BTX) | 6.6 | 3.5% | 78.0% |

| 2013 | Carbon black | 4.6 | 2.4% | 80.4% |

| 20 | Total upper processes (1-18) | 168.4 | 88.6% | |

| 20 | Total chemical industry | 190 | 100% |

Source: CEFIC

When looking at decarbonisation options most of the processes would benefit from replacing the methane with other fuel alternatives such as hydrogen or electrification both of which are available as scalable technologies. And the switch to hydrogen is relatively cost-effective as only smaller tweaks to the existing furnaces are needed.

The World Economic Forum (WEF) and major chemical-sector companies founded the Low-Carbon Emitting Technologies Initiative (LCET) to make concerted decarbonisation efforts across the sector. Their global review proposed expanding the use of public-private partnerships, blended finance and other tailored financial models. The proposition is easy to agree with, but the near-term actions will likely be more guided by the economic reality than long-termism. The decarbonisation efforts in chemical sector are undeniably capital intensive and operating expenses of the new technologies are considerably higher which does not render decarbonisation investment particularly attractive this year. Near term we do not expect a stronger step-up of national governments in the EU to help the industries but funding opportunities will stay open for decarbonisation efforts such as the Innovation Fund and the RePowerEU.

Facing the full enormity of the current supply crisis we have little reason to doubt that the impetus for decarbonisation is waning. It’s hard enough to stay afloat operating the same old technology. But as the gas crisis drags on policy makers can glean important behavioral responses along the chemical value chain that can inform scenario modeling for a better decarbonisation planning. Never let an outsize shock go to waste; improving data capture now will have benefits to reap later.

We would like to point out two major drivers to monitor as the gas crisis drags on. The first is related to crisis management policies. Soon we will learn how the EU plans to handle gas rationing and communicate policy scenarios. Second, the factory shutdowns, production cuts and investment halts can hold important clues about gas demand side adjustments as well as hint at the recession risks and severity in Europe.

More insights

Second high-level impact lunch in Budapest

The Equilibrium Institute held its second high-level impact lunch in the framework of the project on 2 October 2023.

The Industry Taskforce

The Taskforce will pool key decision makers and power brokers from the region to provide expert input, peer review for research and act as ambassadors of the project.